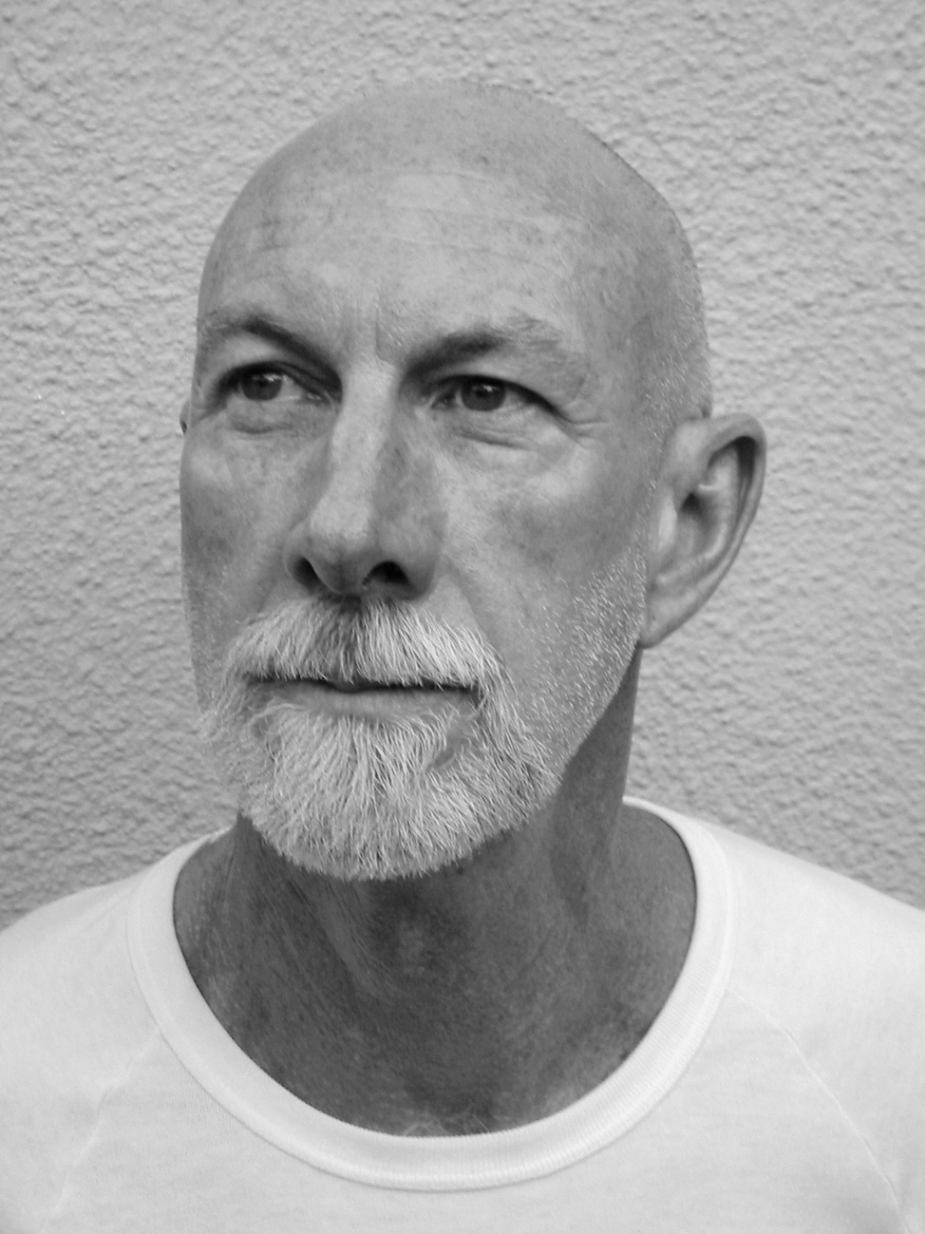

Sudeep Sen

Sudeep Sen read English Literature at the University of Delhi & as an Inlaks Scholar received an MS from the Journalism School at Columbia University (New York). His awards, fellowships & residencies include: Hawthornden Fellowship, Pushcart Prize nomination , BreadLoaf, Pleiades, nlpvf Dutch Foundation for Literature, Ledig House, Wolfsberg UBS Pro Helvetia (Switzerland), Sanskriti (New Delhi), and Tyrone Guthrie Centre (Ireland). He was international writer-in-residence at the Scottish Poetry Library (Edinburgh) & visiting scholar at Harvard University. Sen’s dozen books include: Postmarked India: New & Selected Poems (HarperCollins), Distracted Geographies, Rain, Aria (A K Ramanujan Translation Award), Letters of Glass, and Blue Nude: Poems & Translations 1977-2012 (Jorge Zalamea International Poetry Award) is forthcoming. He has also edited several important anthologies, including: The HarperCollins Book of English Poetry by Indians, The Literary Review Indian Poetry, World Literature Today Writing from Modern India, Midnight’s Grandchildren: Post-Independence English Poetry from India, and others. His poems, translated into over twenty-five languages, have featured in international anthologies by Penguin, HarperCollins, Bloomsbury, Routledge, Norton, Knopf, Everyman, Random House, Macmillan, and Granta. His poetry and literary prose have appeared in the Times Literary Supplement, Newsweek, Guardian, Observer, Independent, Financial Times, London Magazine, Literary Review, Harvard Review, Telegraph, Hindu, Outlook, India Today, and broadcast on bbc, cnn-ibn, ndtv & air. Sen’s recent work appears in New Writing 15 (Granta) and Language for a New Century (Norton). He is the editorial director of Aark Arts and editor of Atlas [www.atlasaarkarts.net].

Sudeep Sen read English Literature at the University of Delhi & as an Inlaks Scholar received an MS from the Journalism School at Columbia University (New York). His awards, fellowships & residencies include: Hawthornden Fellowship, Pushcart Prize nomination , BreadLoaf, Pleiades, nlpvf Dutch Foundation for Literature, Ledig House, Wolfsberg UBS Pro Helvetia (Switzerland), Sanskriti (New Delhi), and Tyrone Guthrie Centre (Ireland). He was international writer-in-residence at the Scottish Poetry Library (Edinburgh) & visiting scholar at Harvard University. Sen’s dozen books include: Postmarked India: New & Selected Poems (HarperCollins), Distracted Geographies, Rain, Aria (A K Ramanujan Translation Award), Letters of Glass, and Blue Nude: Poems & Translations 1977-2012 (Jorge Zalamea International Poetry Award) is forthcoming. He has also edited several important anthologies, including: The HarperCollins Book of English Poetry by Indians, The Literary Review Indian Poetry, World Literature Today Writing from Modern India, Midnight’s Grandchildren: Post-Independence English Poetry from India, and others. His poems, translated into over twenty-five languages, have featured in international anthologies by Penguin, HarperCollins, Bloomsbury, Routledge, Norton, Knopf, Everyman, Random House, Macmillan, and Granta. His poetry and literary prose have appeared in the Times Literary Supplement, Newsweek, Guardian, Observer, Independent, Financial Times, London Magazine, Literary Review, Harvard Review, Telegraph, Hindu, Outlook, India Today, and broadcast on bbc, cnn-ibn, ndtv & air. Sen’s recent work appears in New Writing 15 (Granta) and Language for a New Century (Norton). He is the editorial director of Aark Arts and editor of Atlas [www.atlasaarkarts.net].

Kargil

Ten years on, I came searching for

war signs of the past

expecting remnants—magazine debris,

unexploded shells,

shrapnel

that mark bomb wounds.

I came looking for

ghosts—

people past, skeletons charred,

abandoned

brick-wood-cement

that once housed them.

I could only find whispers—

whispers among the clamour

of a small town outpost

in full throttle—

everyday chores

sketching outward signs

of normality and life.

In that bustle

I spot war-lines of a decade ago—

though the storylines

are kept buried, wrapped

in old newsprint.

There is order amid uneasiness—

the muezzin’s cry,

the monk’s chant—

baritones

merging in their separateness.

At the bus station

black coughs of exhaust

smoke-screens everything.

The roads meet

and after the crossroad ritual

diverge,

skating along the undotted lines

of control.

A porous garland

with cracked beads

adorns Tiger Hill.

Beyond the mountains

are dark memories,

and beyond them

no one knows,

and beyond them

no one wants to know.

Even the flight of birds

that wing over their crests

don’t know which feathers to down.

Chameleon-like

they fly, tracing perfect parabolas.

I look up

and calculate their exact arc

and find instead, a flawed theorem.

Zoji La Pass

at 12,000 feet

slopes steeply. Hard snow

cut into two

by winding tarmac—

a severe cold-slice

freezing to a stand-still.

A car shrinks

through this open-air tunnel—

ice walls on either side—

a geometric strait

resisting

the warmth of diesel’s grey metal.

Two yaks on the lower slopes

look up for colour

in this blinding white.

Their horns storing clues,

anticipating

the mood

of changing temperatures.

In this rarefied air

lungs shrink—

breathtaking breathlessness—

clarified oxygen is sparse here—

high-tone octane echo in the stark terrain.

Yuki

for Bina

In Japanese, Yuki is snow—

unmelted and poised.

She sits askance

in front of a wine-tinged door

whose paint flakes

to expose its wood-raw skin—

pale, seemingly snow-flecked.

Her hair rambles all over

her face, eyes, and neck,

as she stares shyly—

sideways into the distance.

There are secrets locked,

bolted securely

in a shut non-descript studio

in Mumbai,

tucked away somewhere

in Prabha Devi—

as the industrial estate

temporarily quietens

at the allusive

thought of snow herself.

Fantasy instils in

factory-workers, passion—

just as for me—

peeling curls of paint,

a circular chromium lock,

a rusted dis-used bolt,

and breeze that affects

a woman’s hair and lashes,

inspires visions

of snow—

thaw, compassion, desire.

[inspired by a photo by Rafeeq Ellias]

Mediterranean

1

A bright red boat

Yellow capsicums

Blue fishing nets

Ochre fort walls

2

Sahar’s silk blouse

gold and sheer

Her dark black

kohl-lined lashes

3

A street child’s

brown fists

holding the rainbow

in his small grasp

4

My lost memory

white and frozen

now melts colour

ready to refract

Choice

drawing a breath between each

sentence, trailing closely every word.

— James Hoch, ‘Draft’ in Miscreants

1.

some things, I knew,

were beyond choosing:

didu—grandmother—wilting

under cancer’s terminus care.

mama’s mysterious disappearance—

ventilator vibrating, severed

silently, in the hospital’s unkempt dark.

an old friend’s biting silence—unexplained—

promised loyalties melting for profit

abandoning long familial presences of trust.

devi’s jealous heart misreading emails

hacked carefully under cover,

her fingernails ripping

unformed poems, bloodied, scarred—

my diary pages weeping wordlessly—

my children aborted, breathless forever.

2.

these are acts that enact themselves, regardless—

helpless, as i am,

torn asunder permanently, drugged, numbed.

strange love, this is— a salving:

what medics and nurses do.

i live buddha-like, unblinking, a painted vacant smile—

one that stores pain and painlessness—

someone else’s nirvana thrust upon me.

some things I once believed in

are beyond my choosing—

choosing is a choice unavailable to me.

Matrix

for psc

Birds fly across the pale blue sky

cross-stitching a matrix in Pali—

a tongue now beautifully classical

like temple-toned Bharatanatyam.

Dialogues in the other garden

happen not just in springtime. Yet

you stare askance talking poetry

in silence, an angularity of stance

like a shot in a film-noir narrative

yet to be edited down to a whole.

What is a whole? Is it not a sum

of distilled parts, parts one chooses

to expose carefully like raw stock—

controlling patterns in the red light

of dark, a dark that dutifully dissolves.

There emerges at the end,

nests for imaginative flights to rest,

to weave our own stories braving

winds, currents, and the elements

of disguise. Fireflies in the grove

do not belong to numbered generation—

they only light up because line-breaks

like varnam keep purity alive—

enigmatic, disciplined, spontaneous.

Let the birds fly tracing angular paths,

let the dancer dance unbridled,

let the poet write unrestrained—

natural as breathing itself.

Matrix woven can be unwoven—

enjambments like invisible pauses

weave us back into algebraic patterns

that only heart and imagination can.

She walks porcupines—as you do—and

listens to the sound of the sea in a conch.

Grammar

she has no english;

her lips round / in a moan ….

calligraphy of veins ….

— Merlinda Bobis, ‘first night’

My syntax, tightly-wrought—

I struggle to let go,

to let go of its formality,

of my wishbone

desiring juice — its deep marrow,

muscle, and skin.

The sentence finally pronounced —

I am greedy for long drawn-

out vowels, for consonants that

desire lust, tissue, grey-cells.

I am hungry for love,

for pleasure, for flight,

for a story essaying endlessly—words.

A comma decides to pr[e]oposition

a full-stop … ellipses pause, to reflect—

a phrase decides not to reveal

her thoughts after all—ellipses and

semi-colons are strange bed-fellows.

Calligraphy of veins and words

require ink, the ink of breath,

of blood—corpuscles speeding

faster than the loop of serifs …

the unresolved story of our lives

in a fast train without terminals.

I long only for italicised ellipses …

my english is the other, the other

is really english — she has no english;

her lips round / in a moan ….

her narrative grammar-drenched,

silent, rich, etched letters of glass.

Eating Guavas Outside Taj Mahal

The heavy drunken aroma

of fresh guavas

is too sweet for me to bear.

Instead, I drink its nectar

not as liquid-pulp

but as raw unsmooth fruit.

I bite its light-green rough skin

the way I used to

approach a sugarcane stalk

as a child

crunching every fibre

to extract their juice.

There are memories—

memories attached to food

and their consumption.

There are memories

about the rituals of intake—

how certain foods

are allowed or disallowed

depending on God’s stance

and their place

in the lofty hierarchies

they create.

How misplaced these stations

are—God, Emperor, Man

all mistaken—proud errors

of selfhood, status, and ego.

Even under prayer’s veil,

there is something about

eating guavas with unwashed

hands, tasting its taste before

masala, lemon and rock-salt

turn them into sprightly salad—

seed’s bone-crack intentions

slip, cloaked—

buried before they fruit.

Banyan

As winter secrets

melt

with the purple

sun,

what is revealed

is electric—

notes tune

unknown scales,

syntax alters

tongues,

terracotta melts

white,

banyan ribbons

into armatures

as branch-roots

twist, meeting

soil in a circle.

Circuits

glazed

under cloth

carry

alphabets

for a calligrapher’s

nib

italicised

in invisible ink,

letters never

posted,

cartographer’s

map, uncharted—

as phrases fold

so do veils

Alan Gould has published twenty books, comprising novels, collections of poetry and a volume of essays. His most recent novel is The Lakewoman which is presently on the shortlist for the Prime Minister’s Fiction Award, and his most recent volume of poetry is Folk Tunes from Salt Publishing. ‘Works And Days’ comes from a picaresque novel entitled The Poets’ Stairwell, and has been recently completed.

Alan Gould has published twenty books, comprising novels, collections of poetry and a volume of essays. His most recent novel is The Lakewoman which is presently on the shortlist for the Prime Minister’s Fiction Award, and his most recent volume of poetry is Folk Tunes from Salt Publishing. ‘Works And Days’ comes from a picaresque novel entitled The Poets’ Stairwell, and has been recently completed. Maria Takolander’s poetry, fiction and essays have been widely published. She is the author of a book of poems, Ghostly Subjects(Salt, 2009), which was shortlisted for a Queensland Premier’s Literary Award in 2010. She is also the winner of the 2010 Australian Book Review Short Story Competition. She is a Senior Lecturer in Literary Studies and Creative Writing at Deakin University in Geelong.

Maria Takolander’s poetry, fiction and essays have been widely published. She is the author of a book of poems, Ghostly Subjects(Salt, 2009), which was shortlisted for a Queensland Premier’s Literary Award in 2010. She is also the winner of the 2010 Australian Book Review Short Story Competition. She is a Senior Lecturer in Literary Studies and Creative Writing at Deakin University in Geelong.

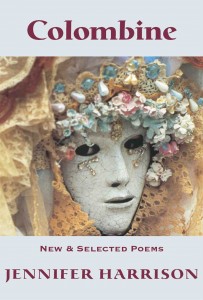

Porch Music

Porch Music

The Domestic Sublime

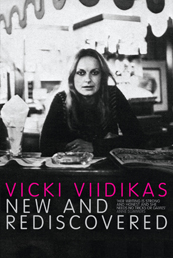

The Domestic Sublime New and Rediscovered

New and Rediscovered

Create Dangerously: The Immigrant Artist At Work

Create Dangerously: The Immigrant Artist At Work The Mary Smokes Boys

The Mary Smokes Boys

.jpg)